The world of U.S. bank regulation is often seen as a landscape of rigid lines and fixed goalposts, where a bank’s fate can be determined by crossing a specific asset threshold. However, a significant shift is underway, championed by both top regulators at the Federal Reserve and key lawmakers on Capitol Hill. They are advocating for a more dynamic, intelligent, and tailored approach to supervision. To help us understand these profound changes, we are joined by Priya Jaiswal, a recognized authority in banking and financial policy. We will explore the push to index regulatory thresholds to economic growth, what a more nuanced, risk-based supervisory model looks like in practice, and how proposed legislation aims to make these common-sense reforms a permanent part of the financial framework.

Tying regulatory asset thresholds to nominal GDP is a key proposal from both regulators and lawmakers. How does this indexing better reflect a bank’s actual risk compared to fixed-dollar thresholds, and what are the immediate operational benefits for banks nearing those legacy benchmarks?

It’s a fundamental move away from a static system that frankly hasn’t kept pace with our economy. Fixed-dollar thresholds, like the $10 billion or $100 billion marks, become arbitrary over time. A $100 billion bank today is not the same entity in terms of its systemic footprint as a $100 billion bank was a decade ago, simply due to inflation and economic growth. Tying these thresholds to nominal GDP creates a self-adjusting framework that is far more robust and resilient. For a bank inching toward one of these cliffs, the immediate benefit is breathing room. The leadership team is no longer forced to make unnatural business decisions just to avoid tripping a wire that triggers a cascade of costly new compliance and capital requirements. It allows for more organic growth and strategic planning without the constant fear of a regulatory penalty for success.

Projections suggest a GDP-indexed system could raise the $100 billion threshold to around $150 billion. Beyond delaying a bank’s transition to a higher regulatory category, what specific strategic opportunities or cost savings does this unlock for growing institutions? Please walk us through the planning implications.

This is about much more than just kicking the can down the road; it’s about unlocking genuine strategic freedom. When you see projections that the $100 billion threshold for Category IV could jump to nearly $150 billion, or the $700 billion mark for Category II could approach $1 trillion, it completely changes a bank’s multi-year planning. We’ve seen institutions engage in complex maneuvers like asset securitizations specifically to manage their balance sheet size and stay below a certain category. With indexed thresholds, that energy and capital can be redirected toward core business functions. A bank can pursue a promising acquisition or invest in a new lending program without that growth being overshadowed by an impending regulatory burden. It allows the C-suite to focus on serving customers and competing in the market, rather than contorting the business to fit a static, outdated regulatory box.

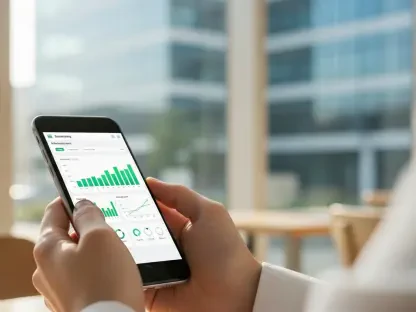

There’s a push for a more nuanced regulatory approach that looks beyond asset size to consider a bank’s business model and risk profile. How might regulators practically implement this during an examination, and what steps should a bank take to demonstrate its unique risk profile effectively?

This is the art of supervision, moving beyond the science of simple numbers. In practice, it means examiners must shift from a checklist mentality to a more holistic, analytical one. They need to ask, “What is the nature of this bank’s business?” A $120 billion bank with a straightforward commercial lending model concentrated in one region carries a very different risk profile than a bank of the same size with complex international operations or significant trading activities. For a bank, the key is proactive storytelling backed by data. It’s not enough to just present your financials. You must build a clear narrative for examiners that explains your business model, articulates your risk appetite, and demonstrates robust internal controls. This means having sophisticated risk management systems that can model various scenarios and show, not just tell, regulators that you understand and are effectively managing your unique risks.

Federal Reserve officials are revisiting supervisory standards, such as CAMELS ratings and the issuance of MRAs, to focus on “material financial risk.” From a compliance standpoint, how does this change the dynamic of a bank examination, and what does the term “material” mean in this context?

This is a game-changer for the tone and focus of bank examinations. For years, there has been a feeling that exams could devolve into “gotcha” exercises over minor issues. The focus on “material financial risk” is an explicit directive to supervisors to concentrate on what truly matters—the issues that could genuinely impair a bank’s safety and soundness or cause harm to the financial system. In this context, “material” means a risk that is significant enough to affect the bank’s financial condition, its capital adequacy, or its management’s ability to run the institution safely. This shift is being implemented through concrete actions, like reviving nonbinding “observations” for less critical issues, which fosters a more collaborative dialogue. It changes the dynamic from purely adversarial to a more constructive conversation about identifying and mitigating the biggest threats, which is what supervision should have been about all along.

Lawmakers are proposing legislation to make these changes permanent. Besides indexing thresholds, what other key provisions in the proposed community banking package would most significantly impact a bank’s day-to-day operations, particularly regarding M&A approvals and capital requirements?

Making these changes permanent through legislation is critical to providing stability and avoiding the regulatory “seesaw” that can occur between different administrations. Beyond indexing, two provisions in the proposed package stand out. First, providing more certainty around the approval process for mergers and acquisitions would have a massive impact. Protracted and uncertain M&A reviews can paralyze strategic planning and add enormous costs. A clearer, more efficient process would be a huge boon for institutions looking to achieve scale and better serve their communities. Second, adjustments to capital requirements, such as recalibrating the community bank leverage ratio down from 9% to 8%, directly impact daily operations. That one-percent change might sound small, but for a community bank, it frees up a significant amount of capital that can be directly deployed as loans to small businesses and families on Main Street.

What is your forecast for the future of bank regulation, especially concerning the balance between tailored supervision for smaller institutions and maintaining systemic stability?

My forecast is that we will continue down this path of “smarter” regulation, not simply more or less regulation. The pendulum is swinging decisively toward tailoring rules to a bank’s actual risk profile rather than relying on blunt, one-size-fits-all asset thresholds. However, this will not be a straight line. The memory of the 2008 financial crisis is long, and there will always be immense pressure to maintain stringent, standardized rules for the largest, most systemically important banks. The real innovation and regulatory focus in the coming years will be on the vast middle tier of regional and community banks. The challenge will be to craft a framework that allows these vital institutions to compete and innovate without creating new, unseen risks. The future is about finding that delicate balance: fostering a dynamic and competitive banking sector while ensuring the entire system remains resilient and stable.